“Hi! I’m here to be operated on!!!” I said to the receptionist, upon walking into the surgery center yesterday morning.

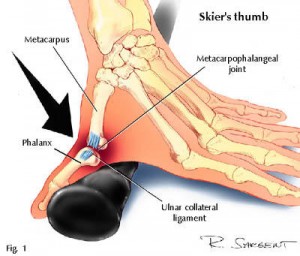

She was expecting me, but I don’t think she was expecting a cheerful me. Granted, it had been 11 hours since my last water or food. But it had been two weeks since I broke my thumb and tore a ligament, so I was anxious to be out of limbo and on the road to recovery.

That was my attitude through the wait, which became FOUR HOURS due to a complication with an earlier patient (spoiler: I had no complications). My friend Deanne and I arrived at 10:15 a.m., and at 10:30 I was taken to a room to change. “We ran out of some gowns and only have XXXL or pediatric. You probably don’t want a mini skirt…” the nurse said. So I put on a gown with a bear print on it — no, I wasn’t seeing a veterinarian — that could have wrapped around me three times, though it ultimately didn’t matter because I was lying on a bed the whole time. The socks were just absurd, even for my size 10 feet, but the nurse found some slightly smaller ones without bear prints on them. The hair net was as attractive as a nun’s habit. Then her assistant struggled valiantly and successfully found my vein (and did much better than the Red Cross people).

Then they let Deanne in the room to keep me company. Their plan was for me to arrive at 10:15 a.m. with a 12:15 p.m. surgery start time. Surgery would last an hour, and recovery would be another hour. I had no choice; diabetics, elderly and young kids get priority due to having to fast since midnight. Well, then a nurse came in and said the doctor was running behind due to “a bump” in the surgery two people ahead of me. We asked how far behind… An hour-and-a half behind! Poor Deanne hadn’t eaten much and was getting a headache, had driven more than two hours just to my house, and yet, she didn’t leave to get food. I felt so bad, but it really was nice to have her company — plus, we don’t catch up as often these days since we live further apart. Our chatter combined with a few texts to pass the time.

The surgeon came in, looked at my hand, and then drew an arrow and initialed it with a Sharpie marker. I asked him about my “good” hand, which had been giving me concern. He looked at it, maneuvered the thumb a bit, and said he thinks it is okay but he’ll X-ray it next week at my post-op visit. The combination of a sprain in that wrist and little strength in that thumb have been wreaking havoc on me, and I suspect some of the pain was in my head. He said to use it as much as I can without too much pain, and that was a huge relief. He left the room and we resumed our wait, though now I was sweating (probably from the anxiety related to my worry about the “good” hand.)

Finally, the OR nurse came in, which I had been told meant that I would be on my way soon. And that’s when honest little ole’ me told the truth when she asked if I was wearing contact lenses. Yes, I was. But they were disposable one-day lenses, I’ve slept in contacts before, and I’ve been wearing them for more than 20 years. Plus, I’m so near-sighted that when woken up from the anesthesia, I wouldn’t be able to see anyone or anything (this is true; I can’t see stoplights without them). She went and talked to the anesthesiologist, who had met me earlier, and I think my good humor, patience and reasoning paid off: I was allowed to keep my contacts! That had been the one thing I really wanted to fight for, so I was happy.

Finally, the OR nurse came in, which I had been told meant that I would be on my way soon. And that’s when honest little ole’ me told the truth when she asked if I was wearing contact lenses. Yes, I was. But they were disposable one-day lenses, I’ve slept in contacts before, and I’ve been wearing them for more than 20 years. Plus, I’m so near-sighted that when woken up from the anesthesia, I wouldn’t be able to see anyone or anything (this is true; I can’t see stoplights without them). She went and talked to the anesthesiologist, who had met me earlier, and I think my good humor, patience and reasoning paid off: I was allowed to keep my contacts! That had been the one thing I really wanted to fight for, so I was happy.

I finally got into the OR around 2:45 p.m. It was chilly in there, which was such a relief. A couple more people introduced themselves and I asked, “Is there going to be a name quiz? Because I’m going to fail. You’re Guy In Mask, right?” I bet they’ve heard every joke by now… Then they put me next to what I now know was the operating table. A guy said something like, “Okay, you can move,” and I had no idea what he meant. “You haven’t done this before??” he asked. “NOPE, this is alllll new to me!” I replied.

The big light fixtures above me were cool and I wished I could take a picture. Then they started looking like doubles and I asked if they had started the anesthesia. The anesthesiologist joked, “It depends.” I think I said something about the lights swimming and he said, “Yes, we did.” And that’s all I remember.

Apparently the doctor came out and talked to Deanne shortly before 4 p.m. Everything had gone as expected, and he had successfully reattached my ligament. Whew! The next thing I knew, I was looking at numbers, which I realized were my vital signs on a machine. The contact lenses were so welcome, because I focused on the heart rate number, watching it go from 50 to 52 to 51 to 50 (yes, I distinctly remember those numbers), probably because I was walking up.

And now the humorous “what I said while waking up from anesthesia” part, as told to me by Deanne: I asked the same questions four times each, including what medicine they had given me. I was happy that nobody had mis-pronounced my name. Then I was insisting to the nurse that I could exercise the next day. She said no because the open wound would get sweaty and probably infected, and that I could miss one week out of 52. The funny thing is, I had known this and intentionally ran 5 miles the previous night so I’d have one last bit of endorphins.

I don’t remember putting on my clothes, but I must have done that, because I didn’t leave in the ridiculous bear gown. And I’ve since learned that the nurse was impressed at how well I did at getting dressed. I’ve also learned that the nurse sat there and went over post-op instructions with Deanne and me, but I don’t remember any of that, either. They took me out to Deanne’s car in a wheelchair (and I didn’t freak out and start hyperventilating like the last time I was in a wheelchair, which is another story). The first thing I really remember is putting my feet on the wheelchair foot rests. Now I understand why they don’t allow patients to go home alone in a taxi.

While I was in surgery, Deanne went to Chipotle. We had some traffic on the drive home, so I was finally in my house and eating around 5:30 p.m., 19 hours since my last meal. That burrito bowl tasted soooo good. I wasn’t in pain, I didn’t feel groggy anymore, it was easy to eat, and I was ravenous. But it took me forever to eat — everything just took so much huge effort.

Deanne was beyond helpful. She’s put up with me for more than a dozen years now, and she drove more than five hours total to help me with surgery. Several other lovely friends offered to help, and any of them would have been amazing. But I doubt they have been through quite as many surgeries as Deanne has, both herself and her family. She brought me food ready to heat up, along with a little container of sour cream because she knows I’m a spice wimp. She stopped at the store for cereal and juice, which I just discovered she pre-opened because my “good” hand can’t really do that stuff. She opened a can for me; she stirred the new jar of peanut butter; she cooked a pizza, cut it and packaged it up; she emptied my dishwasher. She checked my mail and took out my trash. She set medicine alarms on my phone, filled a water bottle, and put it with some of the pills on my nightstand. She arranged pillows so I would elevate my hand overnight.

I went to bed — and proceeded to lie there wide awake. The medication (Norco, aka Vicodin and Tylenol) is notorious for causing drowsiness. Well, that was most certainly not the case here! On the plus side, at 10 p.m. I could call family in a timezone three hours earlier. I also had no problem waking up to the midnight and 4 a.m. medicine alarms, and by 6 I was awake for the day.

I’m going to end this long-winded narrative, since typing is a struggle (now I know to ask about cast thickness when I get a full one next week). But I’ve been amazed at the amount of support and offers for help. From ride offers to Facebook “likes,” I have appreciated every one of them. When I’ve had a couple melt-downs, the support hasn’t faded. I can’t name all of you, but please know that I appreciate it. I can only hope to be as kind as you have been.

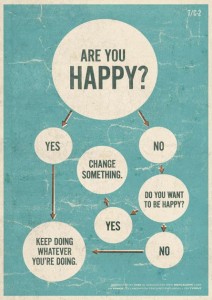

(Found on a blog that linked to this

(Found on a blog that linked to this