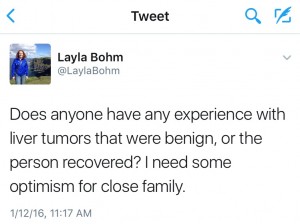

On the afternoon of January 11, 2016, my mother went to the doctor because she had noticed a lump in her abdomen and thought she might have a hernia. The doctor ordered blood work, then scheduled an ultrasound for the next day. That ultrasound was conducted at 11:30 a.m. (9:30 my time), and the doctor immediately ordered a CT scan — not for the next day, but for that same night.

That’s when my mom emailed her three daughters to say her liver appeared to contain multiple tumors.

On January 13, 2016, doctors told my mom that she had four masses in her liver, what looked like another mass in her colon, and that they suspected she had metastatic cancer that had started in her colon. According to the internet search I conducted in about three seconds, that meant she probably had stage four cancer — and there is nothing beyond stage four. Each tumor was the size of a chicken egg. Six days later, I was on a plane to my mom’s house. And the day after that, on January 20, I cried in a hospital room as another doctor, a gastroenterologist who had just conducted a colonoscopy, told us that such cases were “typically inoperable.”

Two things are fairly normal for me: I rarely cry; and most memories are blurry. That day in the hospital defied both norms. One year later, I still clearly remember that room in the Highland Park Hospital. I remember the look on Dr. Chiao’s face, and his struggle to meet my gaze as he watched tears well up in my eyes. I remember trying so very hard to keep those tears at bay, and the maddening frustration as I failed. I remember my mom saying a slow “okay” as the doctor talked. I remember looking at the pictures he had taken during the procedure, and already knowing what they meant because I had been Googling for days. I remember hating the fact that I was sniffling, and that one or two sniffs didn’t suffice. I remember sitting back so that I would be behind my mom and she wouldn’t see me trying so hard to keep control. I remember her, always a mother, looking for a box of tissue, and the doctor handing me a slim, red box. I remember my mom sitting back and saying, “It’s okay, Layla.”

For a long time, things were not okay. A lot of 2016 was not okay. For that matter, the fall of 2015 was also not okay, and my family even said, “things will get better in 2016.” We had no idea.

But that “typically inoperable” phrase didn’t come true for my mother. She rallied and fought back. We went to multiple doctors and surgeons. She jumped through so many hoops in order to start chemotherapy less than three weeks after her first visit to the doctor. I strongly suspect those hoops, maddening and bewildering as they were, saved my mother’s life because, in the three weeks between her first and second CT scans, the tumors in her liver grew half a centimeter each. When colon cancer spreads (metastasizes), it typically goes into the liver and then the lungs, and that’s when it’s finally detected — and by then it’s too late to treat. One of my mom’s tumors was on the outside of her liver, so combined with being a small woman, she noticed it in time.

Chemotherapy, with all of its terrible side effects, stopped the tumors in their tracks. As quickly as they had grown, they began shrinking. Surgeons had various opinions, but my mom chose the liver surgeon who wanted to try teaming up with another surgeon to operate on her colon and liver all at once. Surgeons at a bigger hospital with a big university name hadn’t wanted to attempt such a thing, because that’s just not how it’s done. Even a week before surgery, my mom’s chosen surgeon said they could do the operations separately, but my mom stuck to her decision. Dr. Talamonti, her ever-calming liver surgeon, said “okay, let’s do it.”

On June 2, 2016, surgeons spent six hours operating on my mom’s abdomen. I hung out in the waiting room, later discovering more than one error I made while valiantly attempting to work remotely. I was nearly numb when Dr. Talamonti came to tell me that it was complete and looked good. I think he was expecting me to cry because he had taken me into a private room, but I stuck to my tear-free norm — until he left and I started to walk back to the waiting room. I suddenly turned into the bathroom, and then I cried for the first time since that January day in the hospital.

After nine days in the hospital, my mom went home. Recovery was not easy. And then chemotherapy started again.

On October 31, I was at a beach town in Mexico a couple days before a friend’s destination wedding. I got to a wifi signal and checked my email, knowing my mom was hopefully having her last chemo treatment if it wasn’t postponed, which had happened more than once due to white blood cell counts being too low. My mother had emailed an audio recording of the visit with her cancer doctor, where she received her last chemo treatment and he told her she was done. He then talked about the timing of future CT scans and other maintenance.

And there, beside a pool overlooking the Pacific Ocean in central Mexico, I cried for the third time. My mom was okay.

A good thing:

“Both mild and severe neutropaenia [an abnormally low concentration of neutrophils (white blood cells) in the blood] during chemotherapy are associated with improved survival in patients with MCRC [metastatic colorectal cancer].”

Shitara, K., et al. (2009). Neutropaenia as a prognostic factor in metastatic colorectal cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy with first-line FOLFOX. European Journal Of Cancer, 45(10), 1757-1763. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Keitaro_Matsuo/publication/24010527_Neutropaenia_as_a_prognostic_factor_in_metastatic_colorectal_cancer_patients_undergoing_chemotherapy_with_first-line_FOLFOX/links/555c6a0f08aec5ac2232d3ca.pdf

Hey Layla and Layla’s Mum.

You two were the shining stars of 2016. The ray of hope that some of us clung to in the darkness. Sending love to you both.

Very late comment, but just wanted to say that I’m glad your mom seems to have beaten the odds! Her tenacity surely played an instrumental part.